x

The Weekly Newsmagazine

January 13, 1930

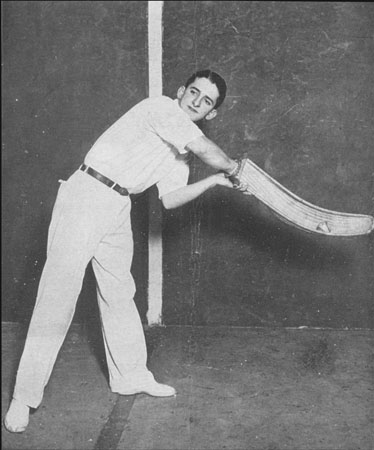

DOMINGO ("THE FOX") UGALDE

Sometimes they have to climb up the screen like monkeys.

(See SPORT)

Jai Alai

(See front cover)

A hard ball flying like a trapped bird in a courtyard with smooth stone walls, its floor marked into divisions by lines and trod by leaping black-haired men -- such was the game the oldtime Aztecs played and drew pictures of on the rock walls of Central American amphitheatres. Hernan Cortés took it back to Andalusia, whence it penetrated the Pyrenees and the people called it pelota (ball). The game became the main diversion of so many festivals that the Basques gave it another name, now mispronounced all over the world, meaning "merry festival" -- jai alai (pronounced high lie).

From wall to wall the little trapped ball, hard as a modern golf ball, smaller than a modern baseball -- a Turk's head of plaited rubber strips sewn in a membrane of goatskin -- flew so hard that it hurt bare hands. The players took to wearing gloves, then invented and strapped to their throwing wrists a long shallow wicker basket (called cesta), hooked like a giant's fingernail. The length of the throwing arc added speed to the little ball, heightened the game's excitement, sent it back across the ocean with other Spanish improvements to Mexico City, where it ranks next to bullfighting; to Havana, where another season of it is now in full stride.

From Havana it reached Miami, where at the Biscayne Fronton matches began again fortnight ago and will continue during the winter visiting time. Nightly, also it is played in the Chicago Fronton on Clark Street and Lawrence Avenue. As the little ball flies the spectators become wildly excited and go home later to tell of the new winter game that has come to the U. S., saying that it is the fastest game in the world.

Technique. The fronton is a three-walled court about two-thirds as long as a football field. As in all court games, a player scores a point by acing his opponent or making him fault. Winning score varies from 6 (elimination singles) to 30 (elimination doubles). In elimination singlesmatches, two players start; when one loses a point he sits down and does not get on the court again until his turn comes. Bets are made on teams, on separate matches, on the length of time one player will hold the court. In a doubles match the players move so fast that without their bright shirts in solid contrasting colors, you could not tell the teams apart. Two rhythms work in jai alai like the separate yet dependent movements of a fugue. One is the sweep of the cesta, catching the ball on the back swing, throwing it the same second with a stab or a sweep, depending upon whether the player wants to make a long shot or a cut. The other rhythm is the movement of the spectators' faces left and right -- first toward the wall as the server, after bouncing the ball, hooks it, swings it back and then forward, sending it away -- then toward the players as the ball leaps back off the wall. The speed of the play is equalled only by its intricacy. The floor is marked off in 12-ft. spaces into certain of which the serve must bounce to be fair, The strength and agility required by a game where the ball moves so fast that the eye can scarcely follow it gives jai alai players astonishing muscles in their forearms.

In Miami. Lou Magnolia, bald-headed, eagle-beaked boxing referee, famed for his catlike springs and crouches and quick thinking in the ring, posed with Mayor Reeder, the Junior Chamber of Commerce band, and a jai alai squad on the steps of Miamis city hall last fortnight. Backed by one Sam Kantor, Magnolia is managing the Biscayne Fronton. Most of the Basque, Cuban and Mexican players in Miami use simplifications of their Latin names -- Martin, Blanco, Ramos, Lopez. The player called Fermin is the only known jai alai man who wears glasses. Passionately, northern visitors compare the merits of Charley and Antonio, favorites of the season last year. Like all jai alai players, Magnolia's youths live in a dormitory. They keep strict training, eat no dinner the nights they are to play. They wear blue and orange uniforms.

Charley and Antonio are back again.

In Havana. Elicia Arguelles keeps a stable of 30 players -- 15 topnotchers at $1,000 a month, 15 beginners at $300. Sometimes he pays a great imported player from Spain as much as $3,000 per month. Through the steep stands, filled with people in straw hats, linen suits and evening dress, under the glaring lights, bookmakers in red caps cry the betting odds as they change on the pari-mutuel system. The walls of the fronton amplify a babel of voices, shouts, steps, the loud breathing of the players, the click of the ball into the cestas and the mocking, metallic plang it makes when it hits the iron wainscots ("tell-tales") on the backwall. Havana players wear duck pants, blue or white shirts. On an average they are heavier, more experienced and higher paid in Havana than in the U. S. In Señor Arguelles' fronton there are two bars going all the time, each famed for special drinks. The Townsen Centre-bar Special is the favorite with U. S. visitors. Before and after a game and between "partidos" the bars are full. As soon as a player steps out to warm up the bars empty. Some good Havana players: Eguiliz ("Eggy") y Gutierrez, who is as big as Babe Ruth and moves with the same easy rhythm, and his rival, Lucio Minore. One of the best players in Cuba is 40 years old. Another is 54.

In Chicago. In Chicago's Fronton are signs "No betting allowed." Near them is where bets (called "contributions" to make them legal) are placed. Alarmed by the rumor that 27 penniless bettors had committed suicide in one week in Havana, the State's Attorney of Cook County once tried with no success to have jai alai banned. Usual odds-on favorite for individual bets is Domingo Ugalde, called "The Fox" because of the sly cuts, curves, angles, backspins he knows how to use. He began playing when he was nine in Marianao, Cuba. He speaks broken, almost unintelligible English. Asked what makes him so good, he points to his head. He is temperamental, histrionic: after losing a close match he has been known to put his fist through a window-pane. Aramendi, Vincente, Garate, Teodoro are other able players, can make Ugalde hump himself. In some Latin countries there are no nets in front of the stands because the spectators feel it would be unsportsmanlike not to risk injury by the ball which can break noses, fracture bones. The Chicago stands are protected. Sometimes the players, running for a hard get and unable to stop, climb up the wire nets like monkeys. Sometimes a fast-running foot goes through a net, annoys box-holding spectators. Unlike players in Havana, those in Chicago are all young: the oldest is 23, the youngest 17. Besides sleeping all in one room. they eat together, go to the theatre together twice a week, jabber constantly in their native tongues, seldom consort with other than their fellow jai alai players.