x

IT'S A BALMY NIGHT in Miami, and you could be dancing under the stars or sipping moonlight cocktails on the beach - but your friends have dragged you to a jai alai fronton. Ho hum.

That's what you think. For inside the fronton the scene is wild - a cross between Hialeah Race Track and hockey night at The Garden - and you soon find you're watching the fastest handball game on earth, with betting to match.

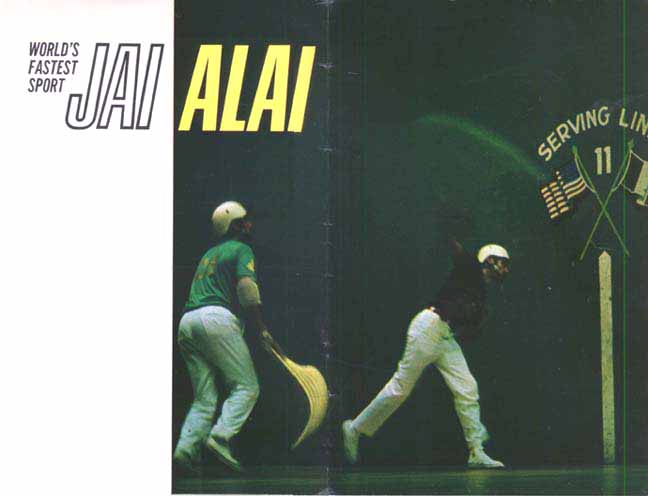

The players, husky South-of-the-Border types, march onto the lighted three-walled court in tennis shoes, white pants and vari-colored shirts, halt at center court, and, in a curious Spanish tradition, lift their cestas - wicked looking curved wicker arm baskets - in a bravado salute to the crowd. In a few seconds, you know why.

The judge's whistle sounds, the number one team's server scoops up a goat-skinned rubber ball in his basket, whips it against the front court wall, and the game is on. Before you can follow the serve, it's been returned, caroming off the side wall and your eyes bulge as a wiry giant goes up that wall like a cat, four or five feet, catches the ball in his basket, and, the instant his feet hit the floor, hurls it back with immense power. His return takes one bounce off the front wall, covers the entire 176-foot court and-crack!-smashes against the back one. Coming out of nowhere, another red-shirted magician fields it backhanded and hurls himself full length on the cement floor to add to the velocity of his 150-mile-an-hour return.

Whip! Crack! Slap - slap-slap. The exchanges continue with seemingly impossible catches and returns for several minutes. Then, a screaming cross court shot, front wall to side, darts out of reach on one blurring bounce - score one.

It's the fastest game on earth, and the betting adds to the excitement, for, like the game, it goes on with seldom a pause. New bets can be made right up to the final sweaty point.

As the serve changes, you check your program and see that most of the names are Basque - which explains why few of the players are cheered by their family names. Even the most fervent aficionado can't cry, "Come on there, Alcibarareichluagi!" or "Arriba, Amuschastegui!"

Whatever their names, they're graceful as cats. The serve alone is a study in ballet. Advancing in a slow trot toward the line, the server bounces the ball several times. Suddenly, he goes into a wheeling dance step, turns his back, bounces the ball once again, scoops it up in his cesta, and, in a lightning blur of unleashed power, slams it against the front wall with a pistol-crack report.

The ball (pelota) is three-quarters the size of a baseball-and as hard as a golf ball. Basically a hand-wound rubber core with layers of wool and string, it's covered by two layers of tough goat skin. At 150 mph, it needs the protection. So do the players - which explains the basket-like cesta they use like something between a glove and a slingshot. And losing sight of the ball for even an instant can be as fatal as standing in front of a speeding train. Men have been killed on the cancha (court), and broken bones are not uncommon.

By a bizarre twist of humor, jai alai in Basque means "happy holiday," for the Basques played it for centuries only on Sunday, bouncing the ball off the wall of the village church.

Under bright lights, the modern cement-floored court stretches 176 by 50 feet, with boarded 40-foot-high front, back and side walls. As in hockey, the spectators are protected by wire screening. The side walls are marked with red numbers, and a serve short of four or past seven loses a point - as does lofting the ball into the screen or dumping it on the foul areas.

The gambling is much the same as on horses or dogs - win, place and show, and the daily double - but in jai alai there are also quinielas, perfectas and the Big Q. In quiniela you bet on two teams to finish first and second, regardless of which is first and which runnerup. In the perfecta, you must select them as they finish. The Big Q is bait for long shot lovers: if you have a first round winner paying, say, $60, your $60 becomes a parlay for the second. If you have nerve enough to pick two long shots that win, you could walk away $15,000 richer.

In Florida, a game consists of five, six or seven points, one less than the number of players (single or double teams) involved. The manager assigns post positions. Numbers one and two play. The loser returns to the bench, and number three takes his place. Play continues until the winner scores the required number of points.

To understand the cheering, you check your program again - and find that those other curious Spanish words people are yelling refer to the players. Since the ball is the pelota, a pelotari is any player. The delantero and zaguero are, respectively, the front and back court men.

Whatever they call them, they're tough. Erdoza Menor, considered one of the greatest pelotaris, dropped dead during a game in his 50's, and Guillermo, called "The Babe Ruth of Jai Alai," was still a formidable competitor in his early 40's. However, most top players are in their 20's.

Antiquarians disagree about the beginnings of this heart-pounding game. Some think it dates back to the Babylonians or Mayan or Aztec Indians, but the first written mention of a pelotari appears in the chronicles of Spain's King Enrique II in 1550. Mainly a Basque sport, the game spread to Cuba, Mexico, Italy, China and the Philippines in the 19th century. Two Cubans introduced it to Florida in 1924.

Because betting was still illegal then in Florida, that first start was inauspicious; when the hurricane of 1926 blew down their flimsy fronton, the Habaneros gave up and went home. But two Miami men built a new one, and in 1935 the legislature passed a pari-mutuel bill, legalizing wagering on the sport. Florida was off to the fronton as well as to the races.

Until 1953, Miami's court was the only one in the state. Now, the sport has spread to Dania, West Palm Beach, Orlando, Tampa and Daytona. From early turnstile figures of less than 1,000,000, attendance grown has to 1,895,313 in 1968-69, with a betting total of $65,842,180. On last season's closing night in Miami, 11,000 fans crowded into a building that seats 6,000 - and bet nearly $400,000 on the games.

If your previous Florida vacations have been all slow motion sun and surf, next time visit a fronton. It'll be a hopped-up holiday, even if you don't win a dollar.