By Andrew Julien, Hartford Courant, 9/13/95

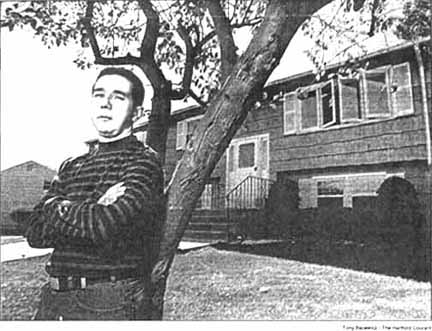

Former Hartford Jai Alai player Daniel Erdocio placed a "for sale" sign on his raised ranch

in Windsor two weeks ago. He plans to move back to France with his wife and three children.

"There's nothing for me here," he said.

The unemployment landscape in Connecticut is littered with men and women with special skills now going to waste: submarine building, jet engine design, vodka bottling.

Add another to the mix: snaring a speeding pelota in a cesta and hurling it into a wall at speeds topping 100 mph.

The shutdown last week of Hartford Jai Alai has thrown 45 players out of their jobs, leaving unanswered a troubling question: What's an unemployed jai alai player to do?

In Daniel Erdocio's case, he'll probably pack up his family and go back to his native France.

"I've got my house on sale right now," he said. "There's nothing for me here,"

Playing jai alai is a special skill bred in the rugged Basque provinces of Spain and France. It would be risky to step onto a court if you didn't know what you were doing.

But outside the protective walls of the jai alai fronton, Erdocio concedes there is little demand for his skills. When the players at Hartford jai alai went on strike some years back, he got by by working as a cook.

This time, he's heading home.

"I'm going back to France, and I'm going to play." Erdocio said. "I feel sad, the way I'm ending it."

Many of the players are still hanging onto the hope that as part of a drive to build a casino in Bridgeport, the state will allow slot machines -- always a crowd pleaser -- at jai alai frontons and dog tracks. If that happens, casino mogul Steve Wynn may bring jai alai back to Hartford.

But that possibility is wrapped up in a complex web of politics and economics swirling around the debate over whether to allow casino gambling in Bridgeport. The legislature is expected to hold a special session in October.

"Politicians are up there screaming and yelling and the whole bit," said Riki Lasa, president of the International Jai Alai Players Association. "Those people don't realize that our lives are hanging in the balance."

Many of the players who've lost their jobs are Basque immigrants. They learned their skills from their fathers, who learned from their fathers, who learned from their fathers. It is not just a game, but a tradition.

Gregorio Altuna, like many young players, was lured to the United States by the promise of good money playing for the crowds in Connecticut. If he is unable to land a spot playing jai alai someplace else, such as Florida, his immigration papers require he return to Spain.

"It's difficult because there's a lot of unemployment in Spain," he said. "I would like to keep playing."

Other players, not as young or flexible as Altuna, are scouring the newspaper's want ads, hoping to find work, said Lasa. The demand for unemployed jai alai players is not expected to be particularly strong. On average, the players at Hartford Jai Alai earned about $30,000 a year.

Lasa, along with others involved in jai alai, blame the Mashantucket Pequots and their glittering Foxwoods Resort Casino near Ledyard for the demise of jai alai in Hartford. Since the late 1980s, attendance and wagering at the North Meadows fronton have dropped sharply.

But Lasa also admits that a prolonged strike some years ago also played a role, though he blames management for taking a hard line during the walkout. "The strike lasted too long," he said. "For us, it was do or die. And if we were going to die, the [owners] were coming with us."

Whether the strike is to blame, or the Pequots, or the legislature's unwillingness to allow slot machines at dog tracks and jai alai frontons, Hartford Jai Alai is silent now.

It is a sad turn of events. Although Hartford's interest in jai alai has waned in recent years, the sport brought a taste of something different to tradition-strapped New England.

And it's sad, too, for the players with nowhere to play.

"If I can't play again jai alai?" asked Altuna, "I don't know. What else can I do?"