x

Off The Wall

HECTORED BY A PLAYERS' STRIKE AND NEW

GAMBLING OPTIONS, JAI-ALAI IS STILL AMERICA'S

PUREST SPORTING EXPERIENCE

By Bruce Schoenfeld

Up close, it's easy to see that Andoni Echaniz is a star. He

carries himself with an animal grace, pacing a hallway on the

balls of his feet like a boxer. Yet he has the look of a model,

which he happens to be on the side, and his quiet charisma fills

a room. A premier player at south Florida's Dania Jai-alai fronton, Echaniz comes from Spain's contentious Basque country, the Pais Vasco, where jai alai is the national sport of a nonexistent nation. Tonight at Dania, he competes only in Games 9 through 12, at the end of the evening, with and against the other standouts. "My goal is to be the best in the world, nothing less," he says. He shakes his head for emphasis, his long curly hair flapping like a flag.

But when Echaniz pulls on the purple shirt of Post 8 and starts

his workday, he becomes anonymous. To the few hundred spectators

scattered throughout the seats on a Wednesday night, Echaniz,

who plays under the nickname Arriaga, isn't one of the finest

young peloteros in the world, a 24-year-old frontcourt master

who represents Dania in competitions against Miami, Milford (Connecticut), Orlando and the few other surviving U.S. frontons. Instead, he and his partner for Game 9, Oyarbide, are merely a win ticket, or half of a quiniela: an investment no more personal than a mutual fund.

If only this were 15 years ago, Arriaga thinks, before the poisonous player strike of 1988 sent the sport on a downward spiral from which it hasn't recovered. Before the tax-free gambling cruises to nowhere began setting sail from nearby harbors and the Lotto jackpots started to multiply and the Native American casinos opened for business with their $10,000 poker hands. Before sports in the south Florida market grew from one major-league franchise to four and South Beach was transformed from a boarded-up slum to a major tourist destination. If it were the mid-'80s, when Dania Jai-alai once managed to gross a $50 million betting handle in a single season and more than a half million in a single night, when cigar smoke filled the fronton and you sometimes had to place bets a game in advance because the lines were so long, 5,000 fans, easy, would crowd the stands on this Wednesday, not just a couple of bus loads of geriatrics and a few hardened regulars.

That 5,000 would include in-the-know tourists, sharply dressed locals, even celebrities, because jai alai mattered back then. While not everyone would instinctively know from watching Arriaga that he has the innate sense of court space and the physical attributes -- strong arm, quick feet -- to become one of the sport's all-time greats, plenty would. They'd be betting him against all comers, running down the odds in game after game. They'd have come out just to see him, for God's sake, like they came out for Churruca and Joey.

Not today. Not these people. "You stink, number five!" someone shouts from the stands at a frontcourt player known as Gallardo, who has just flubbed a seemingly simple catch. Because the fronton is so empty, so devoid of energy or life, everybody hears the heckler, and more than a few patrons chuckle in assent. Because that's what the players are to this perfunctory crowd: mere numbers, numbers that stand for faceless players with unpronounceable Basque names, numbers who change colored shirts and post positions for each game as the odds shift and slide.Andoni Echaniz, who plays under the name Arriaga, is one of jai-alai's foremost

players, but lack of fan appreciation has him toiling in near obscurity.

All photos by Brian Smith.

It's safe to say there's little appreciation in the house right now for Oregi's knack for playing the caroms, or for the canniness of the veteran Alberdi. Or for the nuances that make the sport one of the most compelling in the world for those who have come to appreciate it. "You'd be amazed how many of these people come here, and have been coming for years, and don't even take the time to understand the scoring system," says Brian Sallerson, Dania's public relations and promotions director.The players notice. "When there's 5,000 people watching, certainly we have more drive," Arriaga says. "When there's nobody, like tonight, we have to try to remember that we're professionals and still play our best. It's hard with only 200 people in the stands, especially when they don't understand."

But every now and then, just as if it were 1985 and the stands were filled with true aficionados, Arriaga -- who missed that golden age -- rises to the occasion. Told that he is being watched by a journalist on this night, he steps on the cement court in a controlled frenzy. With his team receiving serve from the brown-shirted Zen, playing for Post 7, Arriaga poaches, swiping the rock-hard ball from the air on one hop with a flick of the wicker cesta that's bound to his right arm, then flings a carom off the side wall at an unretrievable angle. It is like a rocketing tennis serve that somehow is intercepted at net and put away before anyone has time to blink, and it earns Post 8 one point. Equally important, it keeps Arriaga and Oyarbide on the court.

Dania Jai-alai, like the other American frontons, uses a rotational scoring system called Spectacular Seven. It seems complicated, with teams marching on and off every minute or so, but anyone who has ever played pickup basketball will catch on quickly. Lose a rally and you go to the back of the line. Win and you keep the court against the next challengers. The first time each two-man team appears in a game, the rally counts for one point. After one full rotation, when all eight teams have played at least once, points for each rally are doubled. The game ends when one team gets to seven, and whichever teams are second and third at that moment earn place and show. In case of a tie, there's a playoff.

When Arriaga climbs the mesh screen to steal a bounding ball from the air moments later against Post 1 and again transforms it into a two-wall winner, it adds two points to his team's total. But then Oregi of Post 2 throws a sharp-angled putaway of his own, ending Arriaga's and Oyarbide's run and sending them back to the players' booth -- and the end of the line. Five rallies later, their turn up again, Arriaga and Oyarbide stride back onto the court still needing to earn four more points for the game. Two come easily when a player called Cuvet underserves. After a long rally against the next opponents, Arriaga ranges far to his right to cut off a potential winner and bangs the ball off the front wall too hard to be handled. That's seven points, and the victory for Post 8.

There's no reaction from the crowd, other than assorted moans from losing bettors. On the court, too, no emotion is shown for victory just as there is never any shown for defeat, not in public, for that is the Basque way. Arriaga walks off the court like a man heading out to get the mail. He will go to the dressing room and pull off his purple shirt, for the next game begins in a scant six minutes. He glances at the lineup cards taped to a wall in the hallway and notes that in Game 10 he is paired with Yannel in Post 7. This time, his shirt will be brown.

Jai alai is a sport stuck in a time warp.

It may be the purest sports experience left in America, the least

altered from a generation ago. If you like your sports unfettered

by annoying music or commercial announcements, Dania is the place

to go.

Jai alai is a sport stuck in a time warp.

It may be the purest sports experience left in America, the least

altered from a generation ago. If you like your sports unfettered

by annoying music or commercial announcements, Dania is the place

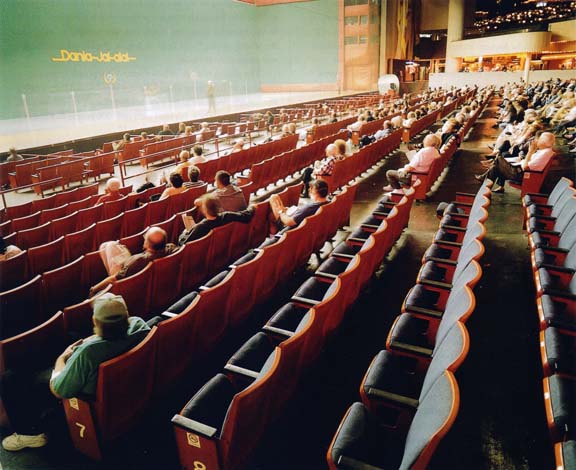

to go.Today, a few hundred fans are scattered about

the seating area at Dania Jai-alai on a typical night.

During the game's heyday, in the mid-1980s, the fronton could

reasonable expect 5,000 fans

who sometimes had to place their bets a game in advance because

the lines were so long.

It isn't for purity's sake that the sport has stayed the same. There's no money and no sponsors. The Dania fronton itself, jai alai's equivalent of a pasha's palace when it opened in 1953, is faded and worn, and positioned for the demographics of a prior day. The site, just off I-95, is prime real estate for a strip mall or a hotel, but far from the area's other tourist attractions. "We're definitely worth more dead than alive," says John Knox, the vice president and general manager. "But even if we wanted to sell the land and move to somewhere that made more sense, we couldn't. Our pari-mutuel license is site-specific. Dog tracks can operate anywhere in a given county, but not us. We have the license to operate on this site, and that's it."

Knox has been working in the business for almost three decades. He understands better than anyone that the proliferation of playing dates that Dania's once-seasonal fronton offers each year in an effort to pay the bills breeds an apathy in the community, a lack of urgency that comes from never needing to go because, as he says, "there's always another chance tomorrow, or next week, or next month." He knows that the hard-core gamblers would rather play poker or slot machines and get an instant return for their wager than sit through the 10 or 15 minutes needed to get a result in a jai alai game. He also knows that the south Florida sports media will never take jai alai seriously, not with Dan Marino and Alonzo Mourning and Pavel Bure in town, though the sport was played in the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. ("We brought all the gold medalists in here right after that and we got no coverage, and no one cared," says Jose Arregui, the player manager at Dania. "It didn't help that American television had showed none of it from Barcelona.")

If professional jai alai, perhaps the most exciting of all pari-mutuel sports, isn't dying in America, it is lingering on life support. Knox reveals that Dania was set to close in July 1998, when a last-minute bill passed the Florida legislature mandating that frontons not be taxed into a position of losing money. Previously, with player salaries, gaming winnings and pari-mutuel taxes added to the cost of running a 300-employee business open for 400 performances a year, the economics were untenable. The new law bought time, but not much. "I'm not painting doom-and-gloom, but something has to change," Knox says. "If we were allowed to reinvent ourselves and use the tools available to any other business in the world, you'd see jai alai survive and thrive. Like this, I'm not sure how long we can go on."

Where once Dania attracted that $50 million seasonal handle, now year-round play accounts for just $30 million. "In the mid-'80s, we were getting 10,000 people in a given night," Knox says. Then, one evening in 1988, the national jai alai players union announced its intention to strike over issues such as full insurance, which Dania's players already had, and a higher percentage of profits.

At the time, the best players in the sport -- Bolivar, Juaristi and the Canadian-born, Miami-based Joey Kornblit, the first great North American star -- were earning well over $100,000 annually. Nobody could understand a strike, but the Basques are famously stubborn. Once they went out on the picket line, there was no way they would back down.

The strike lasted three years, the longest in the history of professional sports. Frontons used substitute players, replacing highly regarded Basques with monikers like Aramayo and Lopetegui with pimply Americans named Rick and Jimmy, which didn't hold quite the same allure. By the time an accord was reached in 1991, habits had changed. Tourists, who had previously made jai alai a mandatory wintertime stop, had found other amusements. Top players had gotten too old or returned to Spain. Laws changed and casinos suddenly flourished nationwide. The south Florida sports fan who might have appreciated jai alai as a sport and a spectacle was now distracted by the wave of big-league xpansion that was just beginning to hit the Sun Belt. Major-league baseball, basketball and hockey all came within a few years, stealing the excitement that once was jai alai's.

Dania has tried hard to cope. It has added low-stakes poker games and video wagering on horse tracks around the country. (In a reciprocal agreement, frontons and tracks carry Dania's feed and handle pari-mutuel wagering on its action as far away as Connecticut, and the additional income helps.) But because the sport isn't televised -- even in a 500-channel cable universe that is starved for programming, jai alai can't find a willing sponsor -- potential fans without access to a betting outlet have no way of knowing which players are emerging as the next stars. "People used to really, really be into jai alai," says Steve Smith, Dania's general manager of mutuels. "But the tourist who came down to Miami and said, 'Let's go see Joey,' doesn't know any of the names anymore. No one player has taken over."

Perhaps that player will be Arriaga. But even as he vows to be the best player in the world, he is having second thoughts about his career choice. Even in the Pais Vasco, jai alai no longer holds the allure that it did.

A half-century ago, the Basques eked out a bare existence farming the stony hills of northern Spain. Their culture was repressed by Franco, and the teaching of Euskera, the Basque language, in schools and even the speaking of it on a city street had been made illegal. Playing jai alai, a school yard game in the Spanish Basque provinces of Vizcaya, Guipuzcoa and Alava and across the French border, was a quietly subversive way to assert your cultural hegemony. And playing it in America was a way to make more money than your father made in his entire life.

Today the Basque region is thriving. Bilbao, its largest city, is a banking and industrial center, and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao has brought millions of tourists and untold dollars. Franco is long gone, and after decades of unsettling terrorism the Basques have gained a measure of autonomy; peace, for the moment, is at hand. Internationalization has brought soccer and even basketball on television, while quelling interest in traditional Basque pursuits. Most Basques are not too different from other Spaniards now. A bullring has even opened in San Sebastian after a 25-year absence.

At the same time, jai alai in America no longer seems like the pot of gold. Salaries in the seven surviving frontons-five in Florida, one in Connecticut, one in Rhode Island-are down to an average of less than $50,000, and some younger players make as little as $25,000. For that, they must play three to five games a night, five to six nights a week plus two to three matinees, 50 weeks a year. "And we're not recognized in the airports," Arriaga says. "At least at home. they know us in the streets of the small towns where we come from. Here, nobody knows who we are. It makes you wonder what we're trying to accomplish."

As with any pari-mutuel, bettors at Dania Jai-alai are not competing against the house, but against each other. They'll bet on the teams (or on individuals, during each night's three singles matches) to win, place or show, or in standard pari-mutuel combinations like quiniela and perfecta. The fronton also offers an increasing number of exotic bets, some that near the point of absurdity. If you win the trifecta in this particular game, and couple it with the quiniela in that particular game, you'll get a jackpot that has been growing since last August. That kind of thing.

At the heart of all of it, of course, is a bettor's belief that one entry will outperform another. But because of the endearing quirks of the Spectacular Seven scoring system, not all post positions are created equal. The one and two positions, which start the game by playing each other, have a decided advantage. The winner holds the court against Post 3, while the loser goes to the end of the line . but will have first crack at double points after each team has played once. By contrast, Posts 6, 7 and 8 are less likely to win, and highly unlikely to combine in quinielas and perfectas. Several weeks into the latest meeting at Dania, for example, the 1-2, 1-3, 1-4 and 1-5 quinielas had all come up between 34 and 38 times, while the 6-7 and 6-8 had each come up only eight times.

If this were purely about numbers, like roulette or blackjack, betting it would be easy enough. But there are individuals playing the game, real athletes. They have a certain amount of talent, a certain amount of inspiration, and rely on a certain amount of luck. "You never know when a player will be affected by something going on in his personal life, a fight with his wife or something like that," says Sallerson, a former player. "When I was at Newport, Rhode Island, and I had friends or family in the stands, I played that much harder. It's natural."

Before the three-year player strike, jai alai's top stars earned more

than $100,000 a year. Today, some players make as little as $25,000.

In an effort to level the play, frontons until recently handicapped each field, putting the better players and teams in the least desirable slots. Only lately have they seen the psychological advantage of giving bettors an improved chance to win, even if the amount won will by necessity be smaller, by allowing the best players to occasionally compete from the best posts. Now, post positions for the pairings are computer-generated, so Arriaga-whose pairing with backcourt player Alex has resulted in eight wins, the most of any team-will go from Post 8 to Post 7 to Post 4 to Post 5 in his four games on this night.

Not that it matters to most bettors anymore. They can't tell the players even with a scorecard. Apparently, they hardly noticed Arriaga's inspired play in Game 9. Teaming with Yannel a few minutes later, he blitzed through Game 10 in a fury, winning four rallies in succession to win that game, too. His team had paid $6.60 in Game 9, but paid an unaccountable $9.20 in Game 10. In Game 12, he added a third-place finish to a rather remarkable night's work.

The following weekend, Dania Jai-alai held a special promotion, an international tournament in conjunction with the Dania Beach Tomato Festival. Players from four Florida frontons were divided up by their nationalities, Basques and Americans and Mexicans and French. The competition attracted a crowd of 2,100, not bad these days. Teamed with back-courter Iru, Arriaga won that one, too, scoring seven straight points for the victory. First prize was $6,000. Perhaps he is coming into his own as the superstar that jai alai so desperately needs. Then again, it might have just been the presence of a dozen employees from the modeling agency he is working with. They had come, at last, to see him play.

Bruce Schoenfeld is a freelance writer living in Colorado.